Photographer and film-maker Aishwarya Arumbakkam spoke to us about history, mythology and the intangible stories that tie them all together

Vani Sriranganayaki

It is a desolate street, a little past midnight – witching hour as they call it. A single street light flickers on and off, in rhythm with the crickets that sound off at a distance. It is misty all around and a slight, cold breeze tickles the nape of the neck. At a distance, a shadow lurks, getting closer and closer with each step. The mist clears just a little bit and the shadow starts to take on a form: it is a lone woman in a white dress that ripples with the breeze. With porcelain-like skin, long hair, black as a thundercloud and dark eyes that pierce through the night, she glides with a luminescent glow around her, searching for something or someone she lost a long time ago. We all have heard these stories, the rumours that get passed on through whispers around a camp fire – tragic accounts of unfulfilled quests for revenge and mysterious incidents that leave even the sanest questioning reality. Although they are meant to be scary and menacing, they almost always recount a tale of unimaginable despair, of a being left to wander the earth, mourning that which is forever lost, or perhaps cautioning those that still have a chance.

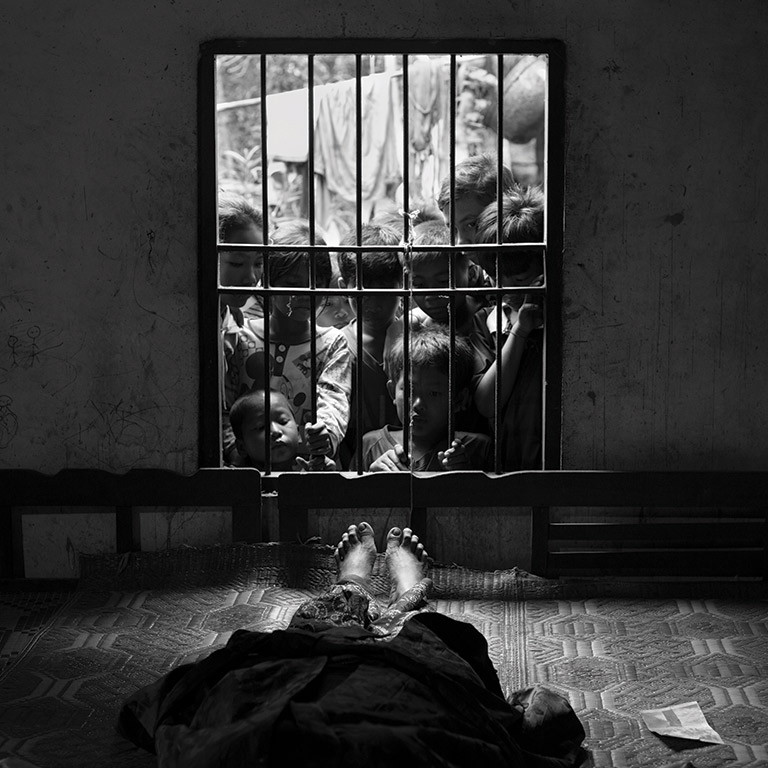

As farfetched as the assessment might seem, to me that seemed to be the hidden intent behind Chennai-born photographer and film-maker Aishwarya Arumbakkam’s works: to unravel stories and find their hidden meanings. Immersed within various themes of perception and identity, her works seamlessly blend together folk tales and many other aspects of life and death; in a concoction that when distilled leaves you with a profound understanding of history, mythology and the cultural narrative that surrounds it all. If the project Ahp, portraying a female spirit character popular in Cambodian folklore and imagination dealt with an identity that is sidelined mostly out of fear, Ka Dingiei talks of a situation where a collective culture is slowly stripped of its space and identity. One feels more real than the other, yet both seem to fashion a similar allegorical approach where mythology, oral histories and realities come face to face with each other, only to reveal meanings and lessons that lurk just beneath the surface. ‘The aspect of photography I connect with most is storytelling. From childhood I’ve understood the world around me through stories, and I still understand it better that way. An important aspect of these communities, and hence the works, is that oral history is very much part of reality. These stories are being shared with me, as oral histories, and then they translate into the works,’ she said.

In a conversation over e-mail, she highlighted the many other forces that propel her work forward, allowing us to dwell deeper into them and find new meanings ourselves.

Excerpts from the conversation

The aesthetic quality in all your works is compelling and nuanced – so much so that they have been called ‘visual poems’. Can you tell us more about your process? Do you visualise certain characteristics of the image beforehand or is it subject to circumstances and the moment?

Thank you, that’s very kind. The visual aesthetics of my work is linked to two things, the content and my position with respect to it. However, it is not a choice I make in a linear manner. Rather it’s something that reveals itself through a series of decisions, and, more importantly, through accidents and mistakes that happen along the process of making the work.

The female identity – both physical and psychological – finds a prominent place in most of your works. What would you attribute this predilection to?

We all navigate through physical and psychological questions about identity. However, being female, South-Asian, and growing up in the subcontinent, these questions occupied the foreground of my psyche. It is perhaps telling that the first few works I made were obsessed with them. When I look back at what these works were, I realise that they were a desperately needed outlet.

Maintaining a sense of emotional distance from their subjects is something that comes a lot when speaking to photographers invested in documenting intimate and personal stories. Do you struggle with it at all? Beyond the artistic scope, does your own narrative ever seep into your photographs?

Regarding emotional distances, I do understand where you’re coming from, but you must understand that I’ve not worked in the realm of what could be traditionally considered as documentary or journalistic photography. On the contrary, in a large sense, the work I do craves to create a certain amount of emotional intensity and connection with the subjects, even if for a moment. Regarding my own narrative seeping into photographs, a lot of the stories featured in my work are stories of communities I am not a part of. I’m conscious of my ethical responsibilities in terms of representation, and I’m also aware that I’m an inevitable filter through which their stories pass. I believe that even absolute objectivity, which in itself seems impossible, is a subjective position an artist takes. And, personally, I’m not one for it.

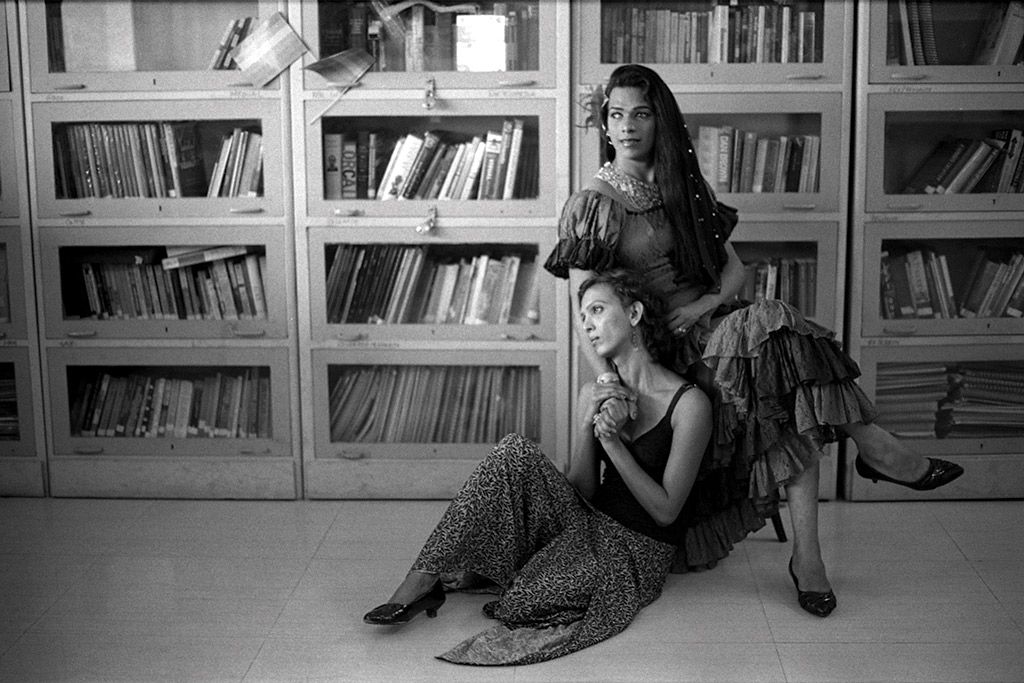

Items’, ‘Stalked’ – they tell the stories that are rarely spoken out loud, but are familiar and relatable. But still, the protagonists in your images demand attention and stand apart from our own perceived ‘understandings’. How do you manage this?

Both these works were about questioning the portrayal of women in popular culture and media, and subverting the mainstream narrative. In Items the women in the portraits demand that you look at them as three-dimensional characters redefining the terms of femininity and sexuality. They take back the term ‘item’ and make it their own. With Stalked, the work was a lot about creating a space for these stories, a space for catharsis.

Coming to Ahp, what was the pull? Can you tell us about what got you started with the project, and the experience of working through it?

I made the work Ahp during the 12th Angkor Photo Workshops at Siem Reap, Cambodia. Perhaps it was because of my obsession with mythologies and oral histories, the character of Ahp revealed itself to me during research, and through interaction with people at Siem Reap and Bakong. It was an intersection between things I was thinking about, and my reaction to the place I found myself in and vice versa. The experience of working on Ahp was honestly a lot of fun. It felt quite similar to working on a film and that’s something I miss at times. A lot of it fell into place as it usually does when you find that one person or image.

Mythology, otherworldliness and horror – Ahp is filled with these themes. But still it seems centred in everyday reality. How did you manage this duality?

In Cambodia, horror as a theme is woven into the country. As a recurring idea in the community’s mythical and psychological landscape, Ahp can be seen as a manifestation of a country’s violent history and the resulting psychological trauma. Hence, it was important to look at the presence or evidence of this horror in everyday life. It was already there, and all I did was perhaps render it physically visible and photograph it.

Finally, what do you personally seek to express through your images?

As cheesy as it sounds, I think what I one day seek to express through my images is that which is indescribable. There is something more, something else. I’ve not had success with translating it as yet, but I hope to get there one day.

All Images Courtesy of Aishwarya Arumbakkam.