by P Abigail Sadhana Rao

In the ruins left by the First World War, when certainty collapsed and the modern world revealed its darker side, an unexpected and fearless movement emerged. It did not try to comfort society or restore order. Instead, it chose to laugh at the very idea of order. That movement was called Dadaism, a bold rebellion that reshaped everything people thought art could be. What draws me to it is the honesty behind its chaos. When the world stopped making sense, Dada artists insisted that art should stop pretending to make sense as well. There is something deeply human in that response. There is grief, anger, humour and a strange kind of clarity.

Dada, as an art movement, began in Zurich in 1916, inside a small and unruly space known as the Cabaret Voltaire. Imagine an intimate room filled with smoke, shouted poetry, strange performances, improvised sounds, and people who had lost faith in the systems that had led to war. They were not simply creating art. They were reacting to a broken world. They were protesting through absurdity. They were refusing to accept the idea that civilisation was still civilised.

That is why Dadaism continues to feel powerful today. It was never only a movement. It was a cultural refusal. Artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Hoch, Raoul Hausmann, Kurt Schwitters, and Max Ernst used absurdity as a weapon and a means of radical protest. They dismantled tradition, questioned logic, mocked beauty, and challenged the belief that art must be refined or rational. Their work was loud, unpredictable, humorous, unsettling, and often surprisingly simple. And in that simplicity, they revealed difficult truths.

Tristan Tzara, one of Dadaism’s founding voices, captured this spirit in his Dada Manifesto (1918),

“Every page must explode, either by profound heavy seriousness, the whirlwind, poetic frenzy, the new, the eternal, the crushing joke, enthusiasm for principles, or by the way in which it is printed.”

For Tzara, Dada was not a manifesto of fixed rules. His own words admitted, “I write a manifesto, and I want nothing, yet I say certain things, and in principle I am against manifestos, as I am also against principles.”

In the defiant flatness of found objects, the chaotic layering of newspaper clippings, and the raw shock of non-sense, Dadaism made art into an act of revolt against order. As Kurt Schwitters later expressed, art could be “a spiritual function of man, which aims at freeing him from life’s chaos.”

Below are five artworks that best embody the shock, clarity, grief, humour, and freedom of Dadaism. Each one reminds us that when reality fractures, art need not glue it back; sometimes it must hold up a mirror.

Duchamp turned the Ordinary into Art

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain remains one of the most disruptive moments in the history of Dadaism. By presenting an ordinary porcelain urinal as an artwork and signing it with the name R. Mutt, Duchamp challenged every assumption about creativity and authority. The exhibition committee rejected it, which only strengthened the work’s power. Duchamp revealed that art did not need to be shaped by the artist’s hand to be meaningful. It could be defined by intention, choice and the courage to question tradition. The simplicity of the act was its boldness. It embodied the spirit of Dadaism, echoing Tristan Tzara’s view that every act of creation must carry either profound seriousness or a crushing joke (Tzara, 1918).

What continues to fascinate me about Fountain is how fully it opened the path for modern and contemporary art. So many movements that followed owe something to this gesture: conceptual art, installation art, performance art and even the playful provocations we see today. It proved that an object does not need beauty or craftsmanship to hold meaning. It only needs an artist willing to ask a difficult question. In the fractured world that emerged after the war, Dadaism allowed artists to confront the absurdity of the times. Duchamp’s Fountain remains a reminder that sometimes the most honest form of creativity is the one that refuses to pretend.

The Power of Hannah Hoch’s Photo Montage

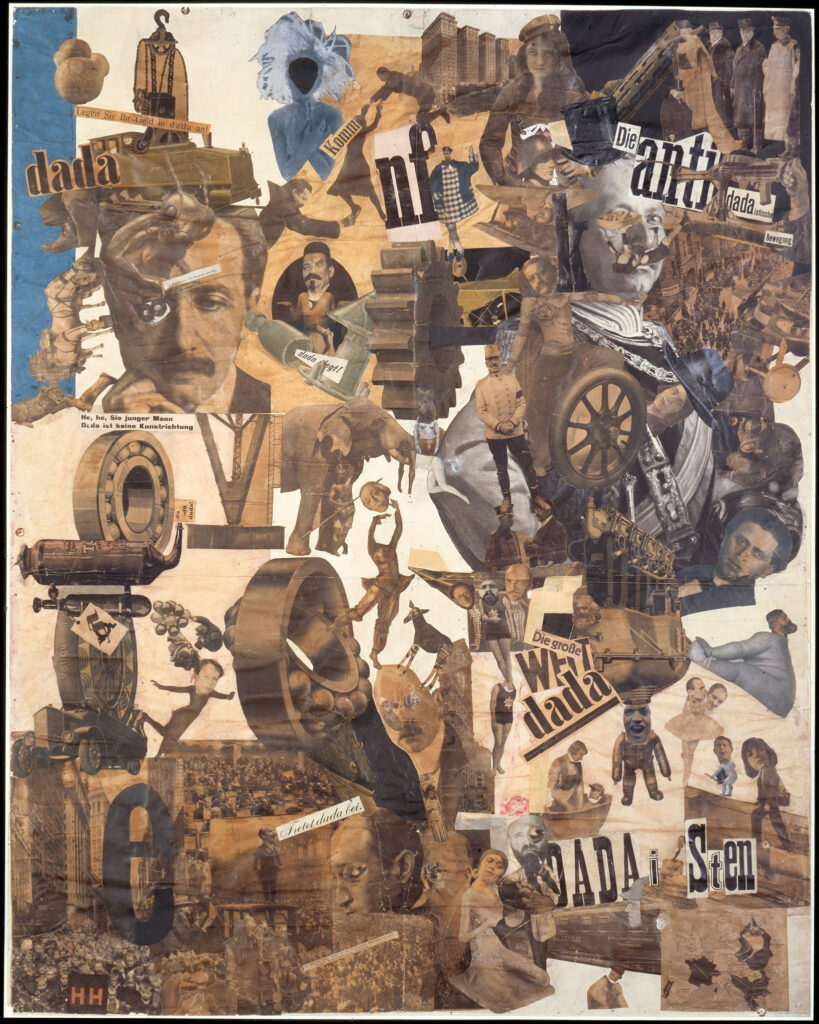

Hannah Hoch stands as one of the most compelling voices within Dadaism, not only for her technical innovation but for the decisiveness and clarity of her vision. Her monumental photomontage Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany slices through the political anxieties, social tensions and contradictions of her time. Hoch gathered fragments from newspapers, magazines and mass media, placing political leaders beside dancers, machine parts and symbols of revolution. The effect is explosive, a deliberate chaos meant to mirror the fractured reality of postwar Germany. What made Hoch’s work so groundbreaking was her ability to use the most ordinary printed images to reveal hidden structures of power. She turned collage into a mirror and a blade.

What moves me most about Hoch’s work is the way she inserts her own voice into a landscape dominated by men. Her “kitchen knife” is not a domestic symbol but a political one. It represents a woman cutting into the thick, suffocating layers of patriarchal and governmental control. Within the dense composition, she places a modest but powerful map showing the countries where women could vote, a detail that quietly shifts the meaning of the entire piece. Her collage becomes an act of rebellion that aligns perfectly with the spirit of Dadaism, which delighted in fragmentation, satire and the refusal to accept any official version of truth. Hoch shows how an artist can confront a turbulent world not only with noise and protest but with precision, intelligence and the courage to see differently.

Raoul Hausmann and The Mechanical Head

The First World War left Europe devastated and stripped of the belief that logic, progress and reason could guide human behaviour toward a better world. In the aftermath of such destruction, Dadaism emerged as a movement that refused to trust the structures that had failed so completely. It stepped forward to ask a deeper and more unsettling question, what remains when reason fails. In a city marked by violence and disillusionment, Raoul Hausmann responded with a radical reimagining of the human head, not as a seat of meaning and soul but as a container of measurement, memory and machinery. His sculpture The Mechanical Head places rulers, a tape measure, a wallet and camera parts across the surface of a hollow wig maker’s dummy, leaving no room for expression or inner life. The result is a portrait of a modern self reshaped entirely by external systems, a figure emptied out and rebuilt according to the logic of its era.

What gives this work its enduring force is the quiet severity of its warning. Hausmann offers no comfort and no path back to a stable self. The head does not look at us, and it does not invite us to look within it. Instead, it shows what happens when a culture becomes so dependent on measurement and order that it forgets the human core that once defined meaning. It exposes the fear that identity might dissolve into functions and tools until the person becomes indistinguishable from the machinery that surrounds them. It remains one of the clearest philosophical statements of Dadaism, a reminder that when reason fails, art must confront the emptiness that rises in its place.

Schwitters and the Birth of Merz

Kurt Schwitters approached Dadaism from a quieter but equally radical direction. Instead of attacking the systems that had failed, he gathered their remains. His work Construction for Noble Ladies is built from fragments of everyday life, including broken wheels, metal scraps, and pieces of discarded toys. He called this method Merz, a word he invented after tearing the fragment “merz” from the German word for commerce, turning it into a name for art created from the remnants of modern society. These rescued fragments become new harmonies in his hands. In a world torn apart, Schwitters chose to assemble meaning from what survived. His works do not shout or protest. They whisper a different form of resilience, suggesting that creation can arise even in the shadow of destruction.

What feels most striking about Schwitters is the tenderness behind his method. Where other Dadaists responded with chaos and confrontation, he responded with reconstruction. His assemblages carry a sense of quiet persistence, as if he were piecing together the fragments of modern life not only to question them but to understand them. Schwitters once wrote that art is a spiritual function that frees us from chaos, and that belief guides the emotional depth of his work. Dadaism always challenged the idea of meaning, yet Schwitters showed that meaning could still be rediscovered in the smallest remnants. His art becomes an act of care, a reminder that even in the aftermath of collapse, beauty waits to be reassembled.

Max Ernst and the Birth of the Absurd

Max Ernst’s Ubu Imperator brings a different kind of Dadaist force, one that stands between rebellion and dream. Painted in 1923, the figure at the centre of the work is part ruler, part child’s toy and part mechanical object. It balances awkwardly in an empty desert, spinning in place with dark authority yet complete absurdity. Ernst draws on Alfred Jarry’s character Ubu, a grotesque parody of political power, to show how leaders can become both ridiculous and dangerous when stripped of humanity. What makes this painting so unsettling is the tension between the playful and the sinister. The desert stretches out silent and indifferent, and the spinning form commands nothing except the space it occupies. This mixture of dream, satire and unease is central to Ernst’s visual language, placing him on the threshold between Dadaism and the Surrealism that would later grow from its spirit.

The deeper power of this work lies in how it captures the instability of authority in a world struggling to rebuild itself. Ernst uses humour but offers no reassurance. The figure has presence but no purpose, authority but no direction, echoing the political confusion of the early twentieth century. Even the landscape is stripped of life, as if the world itself has been wiped clean to reveal only the absurdity of what remains. Dadaism often used fragmentation to challenge rational systems, yet here Ernst turns to the unconscious. His work feels like a dream that knows too much, a landscape that remembers what people would rather forget. It shows how absurdity can be more honest than logic and how art can expose the hollow centre of power by simply revealing its shape. Ernst’s painting stands as a reminder that after the collapse of certainty, the imagination becomes both witness and critic, holding a light to the strange forms authority can take.

When Art Refuses to Behave

The movement that rose from the wreckage of the First World War did not offer comfort or clarity. It emerged from disillusionment, from the recognition that the old certainties had collapsed and that the values that once guided society had fractured beyond repair. The artists who shaped this new vision chose not to mend the broken world through harmony or logic. Instead, they mirrored its contradictions. Duchamp questioned authority with objects taken from everyday life. Hoch sliced through political pretence with a precision few had dared to attempt. Hausmann revealed the erosion of inner life beneath the pressure of modern systems. Schwitters pieced beauty out of fragments others had thrown away, and Ernst exposed the strangeness that lurks beneath the surface of power. Each artist contributed a different way of saying no, a different form of resistance to the expectations of their age.

What continues to make this movement meaningful today is its refusal to follow a single rule or offer an easy truth. In a time that again feels uncertain and crowded with noise, its lessons feel more alive than ever. Art does not need to reassure. It does not need to imitate stability. It can question, provoke, laugh, unsettle, or quietly rebuild. It can reveal the hidden structures that shape us or turn to dreams when reality becomes too rigid to bear. Above all, it reminds us that when logical systems fail, the imagination remains free. The artists who once gathered in small rooms, using scraps, satire, and invention to confront their world, left behind more than a rebellion. They left a reminder that creativity is strongest when it does not behave, when it dares to look at the chaos around it and still find a way to speak.